[ad_1]

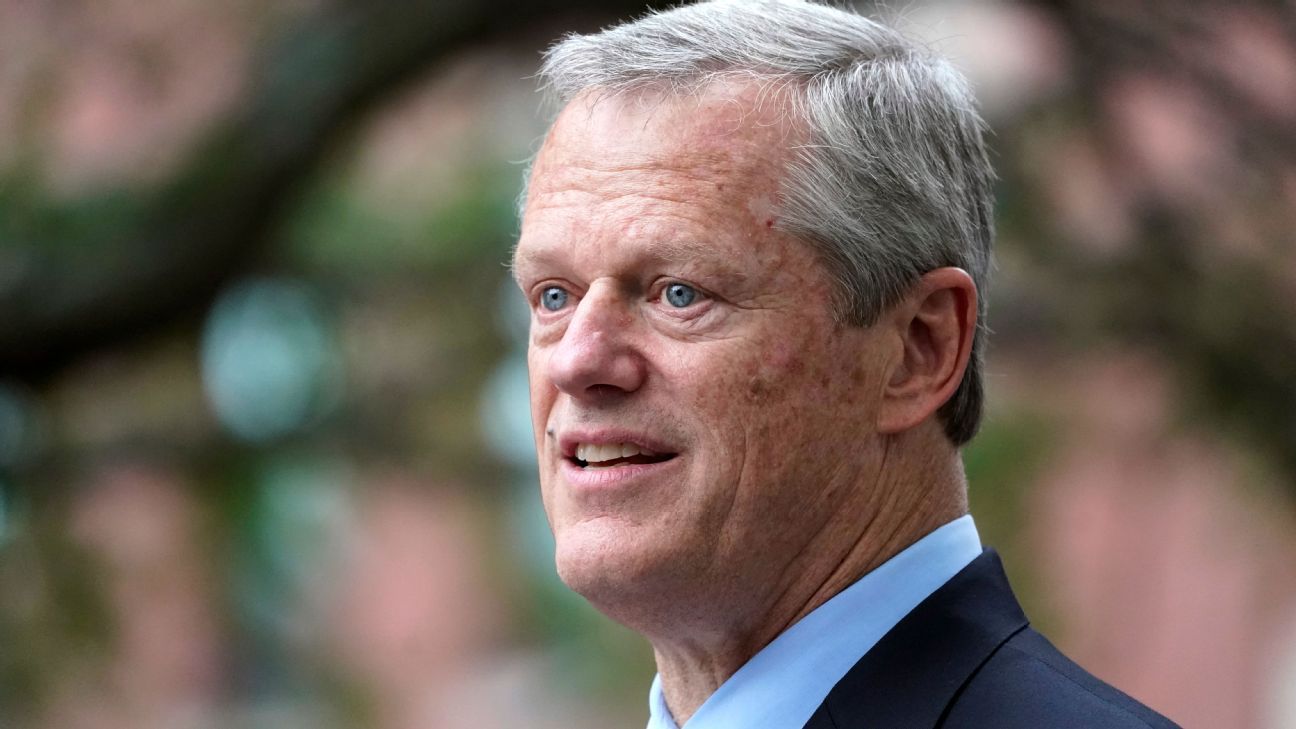

At a Senate hearing Tuesday, NCAA president Charlie Baker shifted the focus of college sports’ needs toward the possibility of athletes being deemed employees of their schools and away from federal legislation to regulate how they can be compensated for their fame.

Baker, Big Ten Commissioner Tony Petitti and Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick were among the witnesses appearing in front of the House Judiciary Committee, the 10th hearing on college sports to be held on Capitol Hill since 2020.

Also appearing were former Florida gymnast Trinity Thomas; Walker Jones, who runs the booster-funded collective that supports University of Mississippi athletes; Saint Joseph’s athletic director Jill Bodensteiner; and Ramogi Huma, a longtime advocate for college athletes.

Baker said in his opening statement that college sports are “overdue for change.”

“But I am proud to say we are doing something about that,” he said.

Baker, the former governor of Massachusetts, touted recent reforms by the NCAA, including more long-term health insurance for athletes, degree completion funds for up to 10 years and scholarship protections.

He also told the committee the NCAA was moving forward with its own regulations for name, image and likeness compensation deals for athletes.

Baker, his predecessor, Mark Emmert and other college sports leaders have been lobbying Congress for help with a federal law to regulate NIL compensation since before the NCAA lifted its ban on NIL payments to athletes in 2021. Several bills have been introduced or made public, including a few bipartisan efforts in recent months, but nothing has gained traction despite what many have referred to as an untenable situation.

“Utah is offering everybody on the team a new truck,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.). “Between the [transfer] portal and NIL, college football is in absolute chaos.”

Meanwhile, legal threats to the collegiate model have emerged. An antitrust case could force schools and conferences that compete at the highest levels of the NCAA into professional-sports-style revenue sharing of billions in media rights dollars with football and basketball players.

The NCAA is composed of more 1,100 schools, serving hundreds of thousands of athletes.

“To enable enhanced benefits while protecting programs from one-size-fits-all actions in the courts, we support codifying current regulatory guidance into law by granting student-athletes special status that would affirm they are not employees,” Baker said.

Baker said athlete representatives from all three NCAA divisions have stated they do not want to be employees of their schools. He said that without congressional action, Division II and III schools might abandon their athletic programs.

Huma, who has been at the forefront of the push for college athletes to receive more benefits and protections, conceded that only major college football and basketball players should be considered for employment status.

The NCAA men’s Division I basketball tournament accounts for most of the association’s annual revenue, which surpassed $1 billion last year, and Power 5 conferences have multibillion-dollar television contracts with most of the value driven by football.

“People are discussing closing the door on employee status without paying the athletes fairly,” Huma said.

Petitti, who became Big Ten commissioner earlier this year after a long career as a television and Major League Baseball executive, said his schools are open to providing more benefits directly to athletes.

The Big Ten signed media rights deals last year that will pay the conference more than $7 billion over the next seven years.

In written testimony, Swarbrick said Congress could consider a “more radical approach” and codify a system in which athletes could negotiate with conferences over terms and conditions of athletic participation.

“They want to know there’s an even playing field; we have to find a way to deliver that to them,” Swarbrick said during the hearing. “That can come either by empowering the NCAA in limited areas to enable competitive equity or to develop a process by which we can agree with our student-athletes on what those rules and regulations should be.”

Bodensteiner, the St. Joe’s AD, said the problems in college sports are impacting only a small part of the enterprise and mostly stem from major college football.

“The reality is, at a Division I school like St. Joe’s, college athletics is actually working quite well,” she said.

Jones’ appearance was the first by someone representing an NIL collective at a congressional hearing on college sports. He said that the booster-backed groups support federal legislation that would preempt state NIL laws and that collectives would like to be involved in the solution.

“I think if we’re doing our part, we can provide really transparent and tangible details to all the stakeholders,” Jones said.

Baker said he was skeptical on collectives helping with transparency, and Petitti expressed concerns about their growing power.

“We are concerned that management of college athletics is shifting away from universities to collectives,” Petitti said.

Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) pushed back on some of the panicked rhetoric about the state of college sports and cautioned against too much government regulation.

“I’d be real careful about inviting Congress to micromanage your business,” Kennedy told Baker.

[ad_2]

Source link